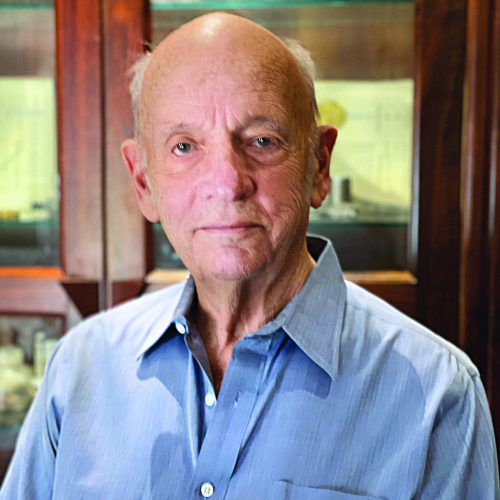

Richard K. Wampler, MD, a renowned innovator and inventor, sought to change the way people thought about rotary blood pumps to support the circulation of patients in heart failure. For decades, his work has reformed the way heart failure is treated today. Dr. Wampler graduated from the Indiana University School of Medicine in 1974 and trained in surgery at the University of Oregon in Portland, Oregon. He enrolled in a Biomedical Engineering program at the University of California at Sacramento in 1980.

Dr. Wampler began focusing on circulatory device work in his junior year of medical school after his grandfather, who was also his mentor, passed away due to heart failure. Since then, he has been a pioneer in the creation of several rotary blood pumps. This included the development and implementation of the Hemopump (the first implantable rotary blood pump) which is known as the Impella. The Thoratec HeartMate II LVAD and the Heartware HVAD are also inventions of Dr. Wampler and were direct results of the Hemopump experience. These technologies would not have happened without Dr. Wampler’s determination and optimism. His circulatory devices are some of the most advanced in the field and have benefited hundreds of thousands of patients.

A Conversation with Dr. Rich Wampler

Henry: Was that relationship with your grandfather a moment that inspired you to look deeper into circulatory device work?

Dr. Wampler: The experience shaped my career and fueled my drive for solutions like those for my grandfather. I challenged conventional ideas. I was only defended by my ignorance. Despite doubts, the Hemopump proved mammalian physiology’s adaptability, even to non-pulsatile circulation and the resilience of blood elements.

Henry: Did that kind of surprise you, or was it expected?

Dr. Wampler: I always believed we didn’t need a pulse, and Leonard Golding’s experiments with two non-pulsatile pumps in calves confirmed it, keeping them alive for 100 days. It boosted my confidence and taught me to trust my ideas. The most impressive observation was the tremendous adaptability of human physiology. During the first human implant it only took a couple of heartbeats for the heart to decide it was OK with no pulse. This has opened an entire field of non-pulsatile physiology. For instance, if there is no pulse a blood pressure cannot be taken with a blood pressure cuff but must be taken with a doppler probe. Likewise, oxygen saturation cannot be taken with a pulse oximeter.

Henry: What were the biggest technical or physiological challenges you faced during the development period?

Dr. Wampler: The things that we thought were going to be hard were not hard, and the things that turned out to be the biggest challenges surprised us. In the beginning we didn’t know what we didn’t know. An expected challenge was sealing the blood from entering the pump mechanism. With the HeartMate 2, we used blood-lubricated bearings instead of seals. This radical approach worked, and after over 100,000 implants, the bearings show no wear, even after 15 years.

Henry: From your clinical experience, did you see a pattern of patients this device benefited the most, and were there ones that it didn’t?

Dr. Wampler: In our first shock trial, the Hemopump flowed at three and a half liters per minute, not five, but still helped a critically ill patient recover. If their heart was ‘stunned’, viable but not beating, it allowed the heart to use less oxygen for beating and more for healing and recovery. Demonstrating that circulation could be supported for short periods of time, investigators started on the path toward mechanical heart replacement -though it’s taken longer than expected, it offers hope for those who can’t get a transplant.

Henry: Did you experience a breakthrough moment during the development process when the key elements aligned, and you realized both the HVAD and Hemopump could become viable, life-saving devices?

Dr. Wampler: With the Hemopump, the first animal experiment convinced me of the proof of principle. As I look back, I strongly believed in rotary pumps driven by a strong intuition that this was the way, but it was based on very little research because the field was in its infancy. I pursued rotary pumps despite a lot of people telling me that if the absence of pulsatility didn’t kill them, hemolysis would. In our first animal experiment, despite setbacks like a broken drive cable and worsening condition of the animal, the Hemopump worked. It normalized blood gases and helped the calf’s lungs recover, convincing me the device could succeed. I learned that taking risks and facing failure are part of innovating and making a difference. I also learned, the hard way, that failure, sometimes soul crushing failure is part of bold journeys

Henry: Was there a moment during the developmental phase when the elements aligned and you realized the device could be put into clinical trials?

Dr Wampler: Not a single moment. In fact, flying to Houston for the first human implant was scary for the team. The engineers, after all, worked on rockets and I had never participated in a clinical trial. In many ways, it was Dr. Frazier’s enthusiasm that propelled me through my doubts.

Henry: What were the challenges and how did you do it?

Dr. Wampler: The team at Nimbus, formerly of Aerojet Liquid Rocket, enlisted a retired rocket pump designer from Aerojet Liquid Rocket to design the first Hemopump hydraulics. I gave him the hydraulic requirements and told him it could only be a quarter inch in diameter. He came back with hand sketches on golden rod paper, and I used them to make 3D models made of mahogany and Bondo. There were no additive manufacturing methods until much later. We adapted a non-thoracotomy bypass concept developed by Willem Kolff, the inventor of dialysis and the total artificial heart. He pioneered passing an inflow cannula retrograde across the aortic valve to empty the left ventricle. The Hemopump leveraged this approach such that the inflow cannula passed retrograde across the aortic valve and connected a small axial flow pump in the aorta. The invention of the Hemopump occurred when I connected the dots of my trip to Egypt where I learned about submersible pump wells, Kolff’s retrograde aortic inflow and the design of rocket axial flow propellant pumps miniaturized.

Henry: How do you feel both HVAD and Hemopump have changed the landscape of treatment for advanced heart failure?

Dr Wampler: It changed the trajectory of mechanical circulatory support, showing that rotary pumps, not positive displacement pumps with valves were the solution. The key innovation was making them durable, which we achieved with blood bearings – without that key discovery, that blood could be used as a lubricant durable pump would not have been possible.

Henry: You mentioned you got to meet some of the families who were touched by your work. What kind of feedback from patients or clinicians has stuck with you the most throughout your career?

Dr Wampler: Dr. Frazier introduced me to Mr. Kranich, who, despite his desperate clinical state in cardiogenic shock, was saved by the Hemopump. I stayed connected with his family, even attended his funeral three years later. I also met Mr. King in Louisville, who was incredibly grateful for the device. A truly humbling moment was attending a banquet with Dr. Adachi at Texas Children’s, surrounded by children saved by my invention, the Heartware HVAD. It was a spiritual high, knowing these kids would have died without it.

Henry: What future technologies excite you the most when it comes to the treatment of heart failure?

Dr Wampler: I’m excited about pharmaceuticals and transgenic hearts, like genetically modified pigs, though a practical solution still far off. LVADs didn’t gain as much traction as I hoped, but I envision a pump that exercises the heart, gradually increasing work and rest periods to eventually promote recovery of the native ventricle and allow pump removal – though no existing pump is safe enough for that yet.

Henry: What advice would you give to future doctors and inventors?

Dr Wampler: Failures can be tough but teach valuable lessons. Goethe’s quote, “Boldness has genius, power, and magic,” has been my mantra all these years. Bud Frazier says if an idea gets pushback, it’s likely a good one. I encourage young people to take risks and be pioneers.

Dr. Wampler gives insight into his current work on circulatory devices:

Dr Wampler: I revisited a 30-year-old idea for a wobbling disk pump, which could lead to a complete artificial heart. Unlike rotary pumps, this positive displacement design doesn’t need valves and offers key advantages, particularly much better blood handling than high-speed rotary blood pumps. We recently completed the first prototype, and it’s exciting. I tell young people to trust their crazy ideas but be prepared for challenges and failure. After all, no one would start anything if they didn’t underestimate the difficulties involved.

Interview conducted by: Henry L. Mentzel, July 2025